Abstract

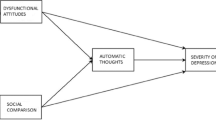

Beck's cognitive theory of depression asserts that active, depressogenic schemas produce a thinking pattern characterized by negative thoughts concerning the self, the world, and the future. Factor II of the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ-30) is assumed to be consistent with two (views of self and future) of the three components of this negative cognitive triad. It was hypothesized that nondepressed subjects exhibiting a high frequency of automatic negative thoughts according to their scores on Factor II would be more sensitive to Velten's Mood Induction Procedure (VMIP) than subjects exhibiting a low frequency of such thoughts. The results indicated that high ATQ-30 Factor II scores predicted significantly more depression on the Depression Adjective Checklist (DACL) and lower psychomotor speed as measured on the Digit Symbol Test. High ATQ-30 Factor II scores had no effect on the Minnesota Clerical Test and the Arithmetic Problems. The results support the view that a high frequency of automatic negative thoughts toward the self and the future in nondepressed subjects may indicate a vulnerability to depression at the moment of testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation.Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87 49–74.

Andrew, D. M., & Paterson, D. (1959).Manual for the Minnesota Clerical Test (rev. ed.). New York: Psychological Corporation.

Beck, A. T. (1976).Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press.

Beck, A. T., Kovacs, M., & Weissman, A. (1975). Hopelessness and suicidal behavior: An overview.Journal of the American Medical Association, 324 1146–1149.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979).Cognitive therapy of depression: A treatment manual. New York: Guilford Press.

Buchwald, A. M., Strack, S., & Coyne, J. C. (1981). Demand characteristics and the Velten mood induction procedure.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49 478–479.

Bumberry, W., Oliver, J. M., & McClure, J. N. (1978). Validation of the Beck Depression Inventory in a university population using psychiatric estimate as a criterion.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46 150–155.

Clark, D. M. (1983). On the induction of depressed mood in the laboratory: Evaluation and comparison of the Velten and musical procedures.Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 5 27–50.

Crandell, C. J., & Chambless, D. L. (1986). The validation of an inventory for measuring depressive thoughts: The Crandell Cognitions Inventory.Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24 403–411.

Dobson, K. S., & Breiter, H. J. (1983). Cognitive assessment of depression: Reliability and validity of three measures.Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 92 107–109.

Goodwin, A. M., & Williams, J. M. G. (1982). Mood-induction research: Its implications for clinical depression.Behaviour Research and Therapy, 20 373–382.

Hollon, S. D., & Kendall, P. C. (1980). Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 4 383–395.

Hollon, S. D., Kendall, P. C., & Lumry, A. (1986). Specificity of depressotypic cognitions in clinical depression.Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95 52–59.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Steinmetz, J. L., Larson, D. W., & Franklin, J. (1981). Depression-related cognitions: Antecedent or consequence?Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90 213–219.

Lubin, B. (1965). Adjective checklists for measurement of depression.Archives of General Psychiatry, 12 57–62.

Lubin, B., Hornstra, R. K., & Love, A. (1974). Course of depressive mood in a psychiatric population upon application for service at 3- and 12-months reinterviews.Psychological Reports, 34 424–426.

Luria, R. (1974). Relationship between mood and digit-symbol performance in hospitalized patients with functional psychiatric disorders.Psychological Medicine, 4 454–459.

Martin, M. (1985). Neuroticism as predisposition toward depression: A cognitive mechanism.Personality and Individual differences, 6 353–365.

Miller, W. R. (1975). Psychological deficit in depression.Psychological Bulletin, 82 238–260.

Polivy, J. (1981). On the induction of emotion in the laboratory: Discrete moods or multiple affect states?Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 41 803–817.

Polivy, J., & Doyle, C. (1980). Laboratory induction of mood states through the reading of self-referent mood statements: Affective changes or demand characteristics?Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 89 286–290.

Pyszczynski, T., Holt, K., & Greenberg, J. (1987). Depression, self-focused attention, and expectancies for positive and negative future life events for self and others.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 994–1001.

Rholes, W. S., Riskind, J. H., & Neville, B. (1985). The relationship of cognitions and hopelessness to depression and anxiety.Social Cognition, 3 36–50.

Riskind, J. H., & Rholes, W. S. (1984). Cognitive accessibility and the capacity of cognitions to predict future depression: A theoretical note.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 8 1–12.

Stiles, T. C., & Götestam, K. G. (1988).Cognitive vulnerability to depression: A longitudinal study. Unpublished manuscript, University of Trondheim.

Stiles, T. C., & Götestam, K. G. (1988). The role of cognitive vulnerability factors in the development of depression. In C. Perris, I. M. Blackburn, & H. Perris (Eds.),Cognitive psychotherapy. Theory and practice. (pp. 120–139). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Teasdale, J. D. (1983). Negative thinking in depression: Cause, effect, or reciprocal relationship.Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 5 3–25.

Velten, E. (1968). A laboratory task for inductions of mood states.Behaviour Research and Therapy, 6 473–482.

Wechsler, D. (1955).Wechsler adult intelligence scale: Manual. New York: Psychological Corporation.

Weissman, A. N., & Beck, A. T. (1978).Development and validation of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale. Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behavioral Therapy, Chicago.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stiles, T.C., Götestam, K.G. The role of automatic negative thoughts in the development of dysphoric mood: An analogue experiment. Cogn Ther Res 13, 161–170 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01173270

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01173270