Summary

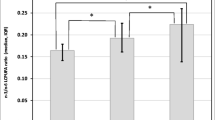

The fatty acid composition of mature human milk from 10 rural Nigerian women was analyzed by high-resolution capillary gas-liquid chromatography and compared to previously determined results on mature human milk from 15 German mothers. Human milk of the Nigerian group contains significantly higher proportions of saturated fatty acids (median 54.07 vs. 42.76% wt/wt). The difference is primarily caused by high values for lauric (C12:0, 8.34%) and myristic acids (C14:0, 9.57%), but not of medium chain fatty acids (C8:0, C10:0), presumably due to increased de novo fatty acid synthesis in the African women consuming a high carbohydrate and low-fat diet. Markedly lower values of oleic and total cismonounsaturated (22.82 vs. 37.98%) as well as trans-isomeric fatty acids (1.20 vs. 4.40%) in Nigerian milk appear to result from low dietary intakes of animal and partially hydrogenated fats, respectively. Although percentage contribution of linoleic acid (18:2n-6) is similar, arachidonic acid (C20:4n-6) and total n-6 long-chain polyunsaturates with 20 and 22 carbons (n-6 LCP) are higher in the African samples. N-6 LCP secretion with human milk lipids is not correlated to the precursor linoleic acid and seems not to depend on maternal dietary intake of preformed dietary LCP with animal fats. N-3 LCP are very high in milk of the Nigerian women who obtain a large portion of dietary lipids from sea fish, but even then docosahexaenoic (C22:6n-3) and not eicosapentaenoic (C20:5n-3) is the predominant n-3 LCP in milk. We conclude that, in addition to dietary effects, metabolic processes regulate the milk content of n-6 and n-3 LCP. We speculate that such metabolic regulation may protect the breastfed infant by providing a relatively constant supply of the physiologically important LCP.

Zusammenfassung

Die Fettsäuren in reifer Muttermilch von 10 Frauen aus einer ländlichen Region Nigerias wurden mit hochauflösender Kapillar-Gaschromatographie untersucht und mit früher erhobenen Ergebnissen aus der Milch von 15 deutschen Frauen verglichen. Die Frauenmilch in Nigeria enthält signifikant höhere Anteile an gesättigten Fettsäuren (Median 54,07 vs. 42,76 Gew.-%). Dieser Unterschied entsteht vorwiegend durch hohe Anteile an Laurin- (C 12:0, 8,34%) und Myristinsäure (C14:0, 9,57%), aber nicht an mittelkettigen Fettsäuren (C8:0, C10:0), wahrscheinlich als Folge einer vermehrten De-novo-Fettsäuresynthese bei den afrikanischen Frauen mit einer kohlenhydratreichen und fettarmen Ernährung. Wesentlich niedrigere Anteile der Ölsäure und der Summe an Monoenfettsäusen (22,82 vs. 37,98%) sowie der trans-isomeren Fettsäuren (1,20 vs. 4,40%) in nigerianischer Frauenmilch dürften aus der niedrigen Nahrungszufuhr an tierischen bzw. partiell gehärteten Fetten resultieren. Obwohl sich in beiden Gruppen ähnliche Gehalte an Linolsäure finden, zeigen die afrikanischen Milchproben höhere Werte für Arachidonsäure und die Summe der n-6-langkettigen Polyenfettsäuren mit 20 und 22 Kohlenstoffatomen (LCP). Der n-6-LCP-Gehalt der Frauenmilch korreliert nicht mit dem Präkursor Linolsäure und scheint nicht von der mütterlichen Nahrungsaufnahme an präformierten LCP aus tierischen Fetten abhängig zu sein. Sehr hohe Werte ergeben sich für n-3-LCP in der Milch der nigerianischen Frauen, bei denen ein relativ großer Anteil der Nahrungsfette durch Seefisch beigetragen wird. Dabei bleibt aber Docosahexaensäure die quantitativ wichtigste n-3-LCP-Fettsäure in der Milch und wird nicht von Eicosapentaensäure verdrängt. Wir folgern, daß der LCP-Gehalt der Frauenmilch nicht allein von der Zusammensetzung der mütterlichen Ernährung abhängt, sondern zusätzlich durch metabolische Prozesse reguliert wird. Wir spekulieren, daß eine solche metabolische Regulation einen Schutzmechanismus für das gestillte Kind darstellen könnte, durch den die kindliche Nahrungszufuhr der physiologisch wichtigen LCP relativ konstant gehalten wird.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- LCP:

-

Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids with 20 and 22 carbon atoms and 2–6 double bonds

References

Carlson SE, Werkman SH, Peeples JM, Cooke RJ, Wilson WM (1991) Plasma phospholipid arachidonic acid and growth and development of preterm infants. In: Koletzko B, Okken A, Rey J, Salle B, van Biervielt JP (eds): Recent advances in infant feeding. Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart (in press)

Crawford MA, Hall B, Laurance BM, Munhambo A (1976) Milk lipids and their variability. Current Med Res Opinion, 4, Suppl 1:33–43

Cuthbertson WFJ (1976) Essential fatty acid requirements in infancy. Am J Clin Nutr 29:559–568

ESPGAN Committee on Nutrition (1991) Aggett PJ, Haschke F, Heine W, Hernell O, Koletzko B, Launiala K, Rey J, Rubino A, Schöch G, Senterre J, Tormo R. Comment on the content and composition of lipids in infant formulas. Acta Paediatr Scand 80:887–896

Finley DA, Lönnerdal B, Dewey KG, Grinetti LE (1985) Breast milk composition: fat content and fatty acid composition in vegetarians and non-vegetarians. Am J Clin Nutr 41:787

Gibson RA, Kneebone GM (1980) Effect of sampling on fatty acid composition of human colostrum. J Nutr 110:1671–1675

Harris WS, Connor WE, Lindsey S (1984) Will dietary w-3 fatty acids change the composition of human milk? Am J Clin Nutr 80:780–785

Haug M, Dieterich I, Laubach C, Reinhardt D, Harzer G (1983) Capillary gas chromatography of fatty acid methyl esters from human milk lipid subclasses. J Chromatogr 279:549–553

Hernell O (1990) The requirements and utilization of fatty acids in the newborn infant. Acta Paediatr Scand, Suppl 365:20–27

Innis SM, Kuhnlein HV (1988) Long-chain n-3 fatty acids in breast milk of Inuit women consuming traditional foods. Early Hum Dev 18:185–189

Insull W, Hirsch J, James T, Ahrens EH (1959) The fatty acid composition of human milk. II. Alterations produced by manipulation of caloric balance and exchange of dietary fats. J Clin Invest 38:443–450

Jensen RG (1989) The lipids of human milk. Boca Raton, CRC Press

Koletzko B, Thiel I, Abiodun PO. The fatty acid composition of human milk in Europe and Africa. J Pediatr (in press)

Koletzko B, Mrotzek M, Bremer HJ (1986) Fat content and cis- and transisomeric fatty acids in human fore- and hindmilk. In: Hamosh M, Goldman AS (eds) Human Lactation 2. Maternal and environmental factors. New York Plenum, pp 589–594

Koletzko B, Abiodun PO, Laryea MD, Schmid S, Bremer HJ (1986) Comparison of fatty acid composition of plasma lipid fractions in well-nourished Nigerian and German infants and toddlers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 5:581–585

Koletzko B, Mrotzek M, Bremer HJ (1987) Trans fatty acids in human milk and infant plasma and tissue. In: Goldman AS, Atkinson S, Hanson LA (eds) Human lactation, Vol 3: Effect of human milk on the recipient infant. Plenum Publishing Corp, New York, pp 323–333

Koletzko B, Mrotzek M, Bremer HJ (1988) Fatty acid composition of mature human milk in Germany. Am J Clin Nutr 47:954–959

Koletzko B, Bremer HJ (1989) Fat content and fatty acid composition of infant formulae. Acta Paediatr Scand 78:513–521

Koletzko B, Schmidt E, Bremer HJ, Haug M, Harzer G (1989) Effects of dietary long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on the essential fatty acid status of premature infants. Eur J Pediatr 148:669–675

Koletzko B (1990) Langkettige Polyenfettsäuren in der Ernährung Frühgeborener. Ernährungsumschau 37:427–432

Koletzko B (1990) Which essential fatty acids should we supply to the parenterally fed newborn infant? In: Ghisolfi J (ed) Essential fatty acids and total parenteral nutrition. John Libbey Eurotext, Paris, pp 123–138

Koletzko B (1991) Zufuhr, Stoffwechsel und biologische Wirkungen transisomerer Fettsäuren bei Säuglingen. Die Nahrung 35:229–283

Koletzko B, Braun M (1991) Arachidonic acid and early human growth: is there a relation? Ann Nutr Metab 35:128–131

Koletzko B. Trans fatty acids may impair biosynthesis of long-chain polyunsaturates and growth in man. Acta Paediatr Scand (in press)

Lauber E, Reinhardt M (1979) Studies on the quality of breast milk during 23 months of lactation in a rural community of the Ivory Coast. Am J Clin Nutr 32:1159–1173

Muskiet FAJ, Hutter NH, Martini I, Jonxis JHP, Offringa PJ, Boersma ER (1987) Comparison of the fatty acid composition of human milk from mothers in Tanzania, Curacao and Surinam. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr 41C:149–159

Prentice A, Jarjou LMA, Drury PJ, Dewit O, Crawford MA (1989) Breast-milk fatty acids of rural Gambian mothers: effects of diet and maternal parity. J Pediatr Gastro Nutr 8:486–490

Read WWC, Lutz PG, Tashjian A (1965) Human milk lipids. II. The influence of dietary carbohydrates and fat on the fatty acids in mature milk. A study in four ethnic groups. Am J Clin Nutr 17:180–183

Ryan BF, Joiner BL, Ryan TA (1985) Minitab handbook. Second ed, PWS-Kent, Boston, MA

Sanders TAB, Ellis FR, Dickerson JWT (1978) Studies of vegans: the fatty acid composition of plasma choline phosphoglycerides, erythrocytes, adipose tissue, and breast milk, and some indicators of susceptibility to ischemic heart disease in vegans and omnivore controls. Am J Clin Nutr 31:805–813

Specker BL, Wey HE, Miller D (1987) Differences in fatty acid composition of human milk in vegetarian and nonvegetarian women: long-term effect of diet. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 6:764–768

Thiemich M (1899) Über den Einfluß der Ernährung und Lebensweise auf die Zusammensetzung der Frauenmilch. Monatsschr Geburtshilfe Gynäkologie 9:504–521

Thompson BJ, Smith S (1985) Biosynthesis of fatty acids by lactating human breast epithelial cells: an evaluation of the contribution to the overall composition of human milk fat. Pediatr Res 19:139–143

Thormar H, Isaacs CE, Brown HR, Barshatzky MR, Pessolano T (1987) Inactivation of enveloped viruses and killing of cells by fatty acids and monoglycerides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 31:27–31

Uauy R, Birch DG, Birch EE, Tyson JE, Hoffman DR (1990) Effect of dietary omega-3 fatty acids on retinal function of very-low-birthweight neonates. Pediatric Research 28:485–492

van der Westhuizen J, Chetty N, Atkinson PM (1988) Fatty acid composition of human milk from South African black mothers consuming a traditional maize diet. Eur J Clin Nutr 42:213–220

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koletzko, B., Thiel, I. & Abiodun, P.O. Fatty acid composition of mature human milk in Nigeria. Z Ernährungswiss 30, 289–297 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01651958

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01651958