Summary

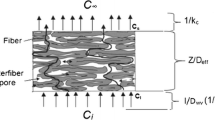

Diffusion can occur in a porous swelling material, such as wood, under three different types of gradients through different parts of the structure. Duffusion of a solute can occur under a concentration gradient through the microscopically visible solvent filled void structure, irrespective of whether the wood swells. When it does swell the wood, additional diffusion can occur through the bound part of the liquid. Diffusion of nonswelling gases and vapors is confined to the microscopically visible voids. It occurs under a vapor pressure gradient. Bound swelling liquids can diffuse through the cell walls under a bound liquid gradient. It is also possible for continuous vapor diffusion through the coarse capillary structure to occur in parallel with continuous bound liquid diffusion through the cell walls. The two may also be in series combination. This necessitates condensation of vapor on a cell wall after passing through the voids under a vapor pressure gradient followed by passage through the cell wall under a bound liquid gradient and re-evaporation into the next void.

These complex combinations of diffusion paths under different motivating gradients have been theoretically analyzed on the basis of diffusion being analogous to electrical conduction where conductivities in parallel are additive and reciprocals of conductivities (resistances) in series are additive. It is thus possible to combine the cross sections and lengths of the different diffusion paths together with separately determined diffusion coefficients on simpler systems in parallel and series combination so as to obtain theoretical combined effective diffusion coefficients.

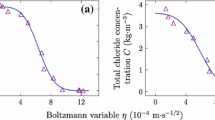

All, or only part, of the six different structures shown in equation (6) may be involved in diffusion through wood. In the case of diffusion of a solute through wood saturated with a swelling solvent, all of the structures are effective. Solution of the equation for diffusion in the fiber direction shows that the fractional fiber cavity cross section almost entirely controls the rate, whereas in the transverse directions the rate is largely controlled by the communicating structure. This is in agreement with experimental diffusion and electrical conductivity measurements, which give diffusion coefficients relative to that of the solute in bulk solvent equal to the fractional fiber cavity cross-section, corrected for the taper of the fibers. The experimental diffusion coefficients, relative to that through the solvent in bulk in the transverse directions, ranged from 0.01...0.06 compared to the elctrical conductivity values of 0.02...0.033, and a theoretical value of 0.0445 over a similar range in specific gravities.

Relative diffusion coefficients for the diffusion of a solute through wood saturated with a non-swelling solvent will be less due to the fact that the terms C a , C e and C c in equation (6) will be zero. These same terms are also eliminated in the diffusion of gases and non-swelling vapors through wood. When all of the diffusion is considered to be free vapor diffusion, the theoretical values are about 30 times the experimental values for transverse diffusion of carbon dioxide, but only about twice for longitudinal diffusion. If the discrepancies are considered to be entirely due to hindered diffusion occurring through the pit membrane openings, hindered diffusion coefficients 1/40 and 1/30 of the free diffusion are obtained, due to the fact that many of the openings are smaller than the mean free path of the gas.

Measurements of the continuous bound water diffusion in the wood substance have been made by filling the voids of the wood with a low fusion metal that expands slightly upon solidification. These values vary but slightly between species and are independent of the specific gravity of the wood, as the E values of equation (14) take the specific gravity into account. The values in the fiber direction are about twice those in the radial direction and three times those in the tangential direction. The diffusion coefficients increase with an increase in temperature in proportion to the vapor pressure of water. This indicates that bound water diffusion must be a molecular phenomenon involving many single molecular jumps rather than being a mass movement of liquid. This is similar to the previously observed diffusion of various bound liquids through polymers [Bagley, Long 1955]. Under conditions where the rate of movement is diffusion controlled, the diffusion coefficients also increase exponentially with an increase in moisture content.

All of the possible paths through wood may be effective both for steady state and dynamic diffusion through wood. The general equation (6) becomes equation (17) which involves free vapor diffusion, hindered vapor diffusion, and bound water diffusion. The logarithm of the theoretically calculated diffusion coefficient varies inversely with the reciprocal of the absolute temperature for a given specific gravity, indicating that a constant activation energy is involved. Experimental diffusion coefficients calculated from moisture gradient, steady state and rate of drying data give values only slightly lower than the theoretical values when corrected to the same specific gravity. When the drying temperatures are corrected from oven temperatures to effective drying temperatures, the agreement is further improved. The fact that the experimental values determined by rate of drying are in quite good agreement with the steady state values, is a good indication that the rate measurements are diffusion controlled.

The evidence here presented clearly indicates the complexity of fluid movement in wood and points out the areas in which further experimentation is desired.

Zusammenfassung

Diffusion tritt in einem porigen quellfähigen Material, wie z. B. Holz, auf, und zwar je nach Art des unterschiedlichen Materialgefüges mit drei verschiedenen Gradienten-Typen. Diffusion eines gelösten Stoffes kann aufgrund eines Konzentrationsgefälles durch die mikroskopisch sichtbaren, mit Lösung gefüllten Hohlräume des Gefüges hindrurch stattfinden, ohne Rücksicht darauf, ob die Lösung das Holz zum Quellen bringt. Bringt sie das Holz zum Quellen, so kann eine zusätzliche Diffusion durch den bis dahin gebundenen Teil der Flüssigkeit stattfinden. Die Diffusion nichtquellender Gase und Dämpfe ist auf die mikroskopisch sichtbaren Hohlräume beschränkt. Sie entsteht durch das Dampfdruckgefälle. Gebundene, quellende Flüssigkeiten können durch Zellwände diffundieren, wenn ein Gefälle gegen die gebundene Flüssigkeit entsteht. Ebenso besteht die Möglichkeit, daß eine kontinuierliche Dampfdiffusion durch die grobe Kapillarstruktur hindurch gleichzeitig mit einer kontinuierlichen Diffusion des gebundenen Flüssigkeitsanteils durch die Zellwand hindurch stattfindet. Beide Erscheinungen können auch in hintereinander folgender Kombination auftreten. Dies setz die Kondensation des Dampfes an der Zellwand nach Durchströmen eines Hohlraumes aufgrund eines Druckgefälles voraus, gefolgt vom Durchtritt durch die Zellwand aufgrund des Gefälles gegen den gebundenen Flüssigkeitsanteil und anschließende neuerliche Verdampfung in den nächsten Hohlraum hinein.

Diese komplexen Kombinationen von Diffusionswegen bei jeweils unterschiedlichen Gefällebedingungen wurden analysiert unter der Annahme einer Analogie zwischen Diffusion und elektrischer Leitfähigkeit, wobei parallelgeschaltete Leitfähigkeiten als additiv und reziproke Leitfähigkeiten, d. h. Widerstände, hintereinandergeschaltet als ebenfalls additiv gelten. Es ist auf diese Weise möglich, Querschnitte und Längen der verschiedenen Diffusionswege zusammen mit gesondert bestimmten Diffusionskoeffizienten auf einfachere Systeme in Parallel-oder Serienanordnung zu übertragen, um dadurch theoretisch ermittelte, kombinierte, effektive Diffusionskoeffizienten zu erhalten.

Bei der Diffusion durch Holz können entweder alle der sechs in Gl. (16) aufgeführten Konstanten oder nur ein Teil von ihnen beteiligt sein. Inden Fällen, bei denen ein gelöster Stoff durch Holz diffundiert, das mit einem quellenden Lösungsmittel gesättigt ist, sind alle Konstanten beteiligt. Die Auflösung der Gleichung für die Diffusion in Faserrichtung zeigt aber, daß der anteilige Querschnitt des Faserhohlraumes nahezu vollständig die Diffusionsgesch windigkeit bestimmt, wogegen bei der Diffusion in den Querrichtungen die Geschwindigkeit weitgehend durch die verbindenden Gefügeteile in dieser Richtung geregelt wird. Diese Erwägungen stehen in Übereinstimmung mit experimentellen Diffusions- und elektrischen Leitfähigkeits-messungen, aus denen sich Diffusionskoeffizienten errechnen lassen, die jenen entsprechen, die für die Diffusion eines gelösten Stoffes im reinen Lösungsmittel zutreffen, was dem anteiligen Querschnitt eines Faserhohlraumes, korrigiert hinsichtlich der spitz zulaufenden Faserenden, gleichzusetzen ist. Die experimentell ermittelten Diffusionskoeffizienten, entsprechend jenen für das reine Lösungsmittel und für Querdiffusion, bewegten sich zwischen 0,01 und 0,06, die elektrischen Leitfähigkeitszahlen liegen im Vergleich dazu zwischen 0,02 und 0,033; schließlich ergibt sich ein theoretischer Wert von 0,0445 für einen vergleichbaren Dichtebereich.

Die entsprechenden Diffusionskoeffizienten für die Diffusion eines gelösten Stoffes durch Holz, das mit einem nichtquellenden Lösungsmittel gesättigt ist, liegen niedriger, weil die Konstanten C a , C e und C c in Gl.(6) Null werden. Sie entfallen ebenso bei der Diffusion von Gasen und nichtquellenden Dämpfen durch Holz. Wird die gesamte Diffusion als freie Dampfdiffusion betrachtet, so erreichen die theoretischen Werte etwa das 30fache der experimentell ermittelten Werte für die Querdiffusion von Kohlendioxyd, allerdings nur das zweifache der experimentellen Werte für die Längsdiffusion. Sofern man sich entschließt, die eben erwähnten Unterschiede gänzlich auf die durch die Tüpfelmembranöffnungen behinderte Diffusion zurückzuführen, so erhält man Koeffizienten der behinderten Diffusion, die 1/40 und 1/30 der freien Diffusion betragen. Dies ist der Tatsache zuzuschreiben, daß viele der in Rechnung gestellten Öffnungen kleiner sind als der angenommene mittlere Durchtrittsquerschnitt. Messungen zur Diffusion des gebundenen Wassers in die Holzsubstanz wurden in der Weise durchgeführt, daß man die Hohlräume des Holzes mit einem leicht schmelzenden Metall füllte, das sich bei der Verfestigung nur sehr wenig ausdehnt. Die erhaltenen Werte schwanken nur wenig zwischen den einzelnen Holzarten und erweisen sich als unabhängig von der Dichte des Holzes, da die E-Werte der Gl. (14) die Dichte in Rechnung stellen. Die Diffusionswerte in Faserrichtung betragen etwa das zweifache jener in Radialrichtung und das dreifache jener in Tagentialrichtung. Die Diffusionskeoffizienten wachsen mit steigender Temperatur proportional zum Dampfdruck des Wassers an. Dies gibt einen Hinweis darauf, daß die Diffusion gebundenen Wassers eher den Charakter einer molekularen Erscheinung hat, die ihrerseits eine Reihe von einfachen molekularen Verbindungsschritten einschließt, als denjenigen der Bewegung einer Flüssigkeitsmasse. Diese Vorgänge besitzen also Ähnlichkeit mit der schon früher beobachteten und geschilderten Diffusion verschiedener gebundener Flüssigkeiten durch Polymere [Bagley, Long 1955]. Unter der Bedingung, daß die Bewegungsgesch windigkeit durch Diffusion gesteuert wird, wachsen die Diffusionskoeffizienten ebenfalls exponentiell mit dem Anstieg des Feuchtigkeitsgehaltes.

Alle der möglichen Diffusionswege durch das Holz sind sowohl bei ruhender und dynamischer Diffusion wirksam. Die allgemeine Gleichung (6) wird zur Gl. (17), welche die freie Dampfdiffusion, die behinderte Dampfdiffusion und die Duffusion gebundenen Wassers einschließt. Der Logarithmus des theoretisch errechneten Diffusionskoeffizienten ändert sich im umgekehreten Sinne mit dem reziproken Wert der absoluten Temperature bei einer gegebenen Dichte, was darauf hinweist, daß an dem Vorgang eine konstante Aktivierungsenergie beteiligt ist. Experimentelle Diffusionskoeffizienten, die mit Hilfe des Feuchtigkeitsgefälles, des Fauchtigkeitsgleichgewichts und der Trocknungsgeschwindigkeit errechnet wurden, ergeben Werte, die nur wenig unter den theoretischen Werten liegen, soferndiese auf die gleiche Dichte korrigiert wurden. Korrigiert man ferner die Trocknungstemperturen, und zwar von den Kammertemperaturen auf die tatsächlichen Trocknungstemperaturen, so wird die Übereinstimmung der Werte nochmals verbessert. Die Tatsache, daß die experimentell mit Hilfe der Trocknungsgeschwindigkeit bestimmten Werte gut mit den Feuchtigkeits-Gleichgewichtswerten übereinstimmen, gibt einen deutlichen Hinweis darauf, daß die Messungen der Trocknungsgeschwindigkeit durch die Diffusion bestimmt sind.

Die hier angegebenen Beweise zeigen ziemlich klar die Komplexität der Flüssigkeitsbewegung in Holz auf und lassen jene Gebiete erkennen, in denen weitere experimentelle Forschung sinnvoll erscheint.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bagley, E., and F. A. Long: J. Am. Chem. Soc. Vol. 77 (1955) p. 2172

Barkas, W. W.: The Swelling of Wood under Stress. London 1949: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

Barrer, R. M.: Diffusion in and through Solids. London 1941: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Bateman, E., J. P. Hohf and A. J. Stamm: Ind. Eng. Chem. Vol. 31 (1939) p. 1150

Behr, E. A., D. R. Briggs and F. H.Kawfort: J. Phys. Chem. Vol. 57 (1953) p. 476.

Biggerstaff, T.: Forest Products J. Vol. 15 (1965) (3) p. 127.

Burr, H. K., and A. J. Stamm: J. Phys. Colloid Chem. Vol. 51 (1947) p. 240.

Cady, L. C.: Molecular Diffusion into Wood. Ph.D. Thesis, U. of Wisconsin, Madison, Wis. (1934).

— and J. W. Williams: J. Phys. Chem. Vol. 39 (1935) p. 87.

Choong, E. T.: Forest Products J. Vol. 15 (1965) (1) p. 21.

Christensen, G. H.: J. Australian Council for Sci. Ind. Research Vol. 18 (1945) p. 407.

—, and E. V. Williams: Australian J. Appl. Sci. Vol. 2 (1951) pp. 401, 430, 440.

—: Australian J. Appl. Sci. Vol. 11 (1960) p. 294.

—, and K. E. Kelsey: Holz Roh- u. Werkstoff Vol. 17 (1959) p. 178.

Comstock, G. L.: Forest Prod. J. Vol. 13 (1963) p. 97.

Crank, J.: The Mathematics of Diffusion. London 1956: Clarendon Press.

Egner, K.: Forschungsber. Holz Vol. 2 (Berlin 1934).

Elers, T. L.: Forest Products J. Vol. 15 (1965) (3) p. 134.

Forest Products Research, Great Britain Dept. Sci. Ind. Research. London 1960–61: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

Friedman, L., and E. O. Kraemer: J. Am. Chem.Soc. Vol. 52 (1930) p. 1295.

Hann, R. A.: Ph. D. Thesis entitled: A Fundamental Investigation of the Drying of Wood at Temperatures above 100 Degrees Centigrade. Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Wood Science and Technology of North Carolina State University, June 1965.

Hart, C. A.: Forest Prod. J. Vol. 14 (1964a) (1) p. 25.

—: Forest Prod. J. Vol. 14 (1964b) (5) p. 207.

Hermans, P. H.: Contributions to the Physics of Cellulose Fibers. Amsterdam, and New York 1946: Elsevier Publishing.

Jost, W.: Diffusion in Solids, Liquids and Gases. New York 1952: Academic Press.

Kollmann, F.: Forsch. Geb. Ingenieurw. Vol. 6 (1935) p. 169; Vol. 7 (1936) p. 113.

Lusby, G. R., and O. Maass: Canadian J. Research Vol. 10 (1934) p. 180.

March, H. W., and W. Weaver: Phys. Rev. Vol. 31 (1928 p. 1072.

Martley, J. F.: Gt. Britain Dept. Sci. Ind. Res., Forest Prod. Research Tech. Paper No. 2 (1926).

Newman, A. B.: Cooper Union Bull., Eng. Sci. No. 5 (1932).

Prager, S., and F. S. Long: J. Am. Chem. Soc. Vol. 73 (1951) p. 4072.

Sherwood, T. K.: Ind. Eng. Chem., 21 (1929) p. 12.

Sherwood, T. K., and E. W. Comings: Vssesayuznovo Toplotechnisches Kovo Inst. Vol. 8 (August 1929).

Skaar, C.: Forest Prod. J. Vol. 8 (1958) (12) p. 352.

Stamm, A. J.: J. Agr. Research Vol. 38 (1929) p. 23.

Stamm, A. J.: U. S. Dept. Agr. Tech. Bull. No. 929 (1946).

—: J. Phys. Chem. Vol. 60 (1956a) p. 76.

—: Proc. Australian Pulp & Paper Ind. Tech. Assoc. Vol. 10 (1956b) p. 346.

—: Forest Prod. J. Vol. 9 (1959) p. 27.

—: Forest Prod. J. Vol. 10 (1960) p. 524.

—: Wood and Cellulose-Liquid Relationships, Prt. 4, Tech. Bull. No. 150, North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station, Raleigh, N. C. (Sept. 1962).

—: Forest Prod. J. Vol. 14 (1964a) (9) p. 403.

—: Wood and Cellulose Science. Ronald Press Co., New York 1964b, Ch. 3, 12, 15, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23.

—: TAPPI Vol. 48 (1965) (10) p. 598.

—, and R. M. Nelson, Jr.: Forest Products J. Vol. 11 (1961). p. 536.

—, and M. Wilkinson: TAPPI. Vol. 48 (1965) (10) p. 578.

Stillwell, S. T. C.: Gt. Britain Dept. Sci.: Ind. Research, Forest Products Research Paper No. 1 (1926).

Tarkow, H., and A. J. Stamm: Forest Products J. Vol. 10 (1960) (5) p. 247, (6) p. 323.

Tuttle, F.: J. Franklin Inst. Vol. 200 (1925) p. 609.

Yakota, T.: J. Japan. Wood Research Soc. Vol. 5 (1959) (4) p. 143.

Wirakusumah, S.: Comparison between the Experimental and Theoretical Drying Diffusion Coefficients for Softwoods and Hardwoods. MS Thesis, Department of Wood Science & Technology, North Carolina State of the University of North Carolina, Raleigh, N. C. (1962).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stamm, A.J. Diffusion. Wood Sci.Technol. 1, 205–230 (1967). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00350462

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00350462